Q: Describe your background and what brought you to the Wilson Center.

I am a Ukrainian art historian, artist, and curator, currently based in Mexico. I hold a PhD in History of Art awarded by the Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London. My academic interests extend from East European to Latin American art history in its intersection with political history of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries and the application of postcolonial and decolonial theories in the post-Soviet space and the Global South. In my research, I aim to establish the methodology of art historical comparative studies (a perspective that is present in literary and political studies but currently underdeveloped in art history) and to propose a decolonial perspective on modern and contemporary Ukrainian art practices within the larger case of dismantling post-Soviet space. Since the full-scale invasion began on February 24, 2022, the focus of the development of decolonial studies in relation to Ukrainian history and culture has become my main priority. My current main focus of research is the cultural impact of Russia’s war against Ukraine and the ways in which the ongoing anti-colonial resistance together with Ukraine’s decolonial release transformed Ukrainian art after 2014.

Currently, I am working on two books. I am compiling an edited volume, Art in Ukraine: Between Identity Construction and Anti-Colonial Resistance, which gathers texts from Ukrainian and international art historians, art critics, and curators. I'm also working on a monograph, Ambicoloniality and the War: The Ukrainian-Russian Case, that for the first time addresses post- and decolonial processes in Ukraine and Russia and the effects of the dismantling of the post-Soviet space since the outbreak of the war in 2014. For both books, I have signed the contract for publication with two major international publishers to see light between late 2023 and early 2024.

Q: What project are you working on at the Center?

On the kind invitation of the Kennan Institute, I focus on the role of art institutions in the decolonization processes in Ukraine and explore how the institutional structure has changed after 2014. In this research, I discuss which impact the development of art and cultural institutions of different levels – from non-profit grassroots initiatives to public institutions – has on Ukraine’s disentanglement from Russia’s former colonial domination. I will further incorporate this text into my forthcoming book, Ambicoloniality and War. The focus on the importance of cultural institutions for the process of decolonization is recurring in my research because I believe that it is important to look at different aspects of artistic and cultural development in a local context, which in the case of Ukraine is fostered by the traumatic events of the war which brought about a wider understanding of cultural decentralization. Here, I refer to what Polish art historian Piotr Piotrowski called “horizontal art history”, an approach reflecting on local complexity and polyphony. The institutional transformation in culture constitutes this horizontal locality most pragmatically and permits linking the changing decolonial narratives to a more profound tectonic shift in identity without losing cultural diversity from sight. That is why I dedicate much attention to the questions of institutions in my research on decolonization.

Q: How did you become interested in your current research topic?

The first research event I organized on Ukrainian art and its contribution to resistance and resilience in the war took place at the Courtauld Institute of Art in 2015. It was the first international symposium of Ukrainian Art Now: Spaces of Identity dedicated to contemporary practices in Ukrainian art in the UK at that time, which proves the recent degree of invisibility of Ukrainian culture internationally. Since then, I have extensively worked with Ukrainian art, as researcher, curator, and artist. As an artist, I presented a long-lasting project The Morphology of War (2017), a large-scale graphic series, in which I discuss the creation of the image of “the other” as an inevitable result of postcolonial ambivalence and hybridity that was found in the Ukrainian society from the dissolution of the Soviet Union and up until 2022. In 2021, three months before the invasion, I published an edited volume, Contemporary Ukrainian and Baltic Art. Political and Social Perspectives, 1911-2021, where prominent Ukrainian, Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian scholars and curators participated. In the introduction to my edited book, I spoke about the parallels that can be made between Ukrainian and Baltic art practices through the notions of historical trauma, contested identity, and the reconsideration of belonging to the post-Soviet space. The open full-scale aggression of Russia in 2022 showed it is no more possible to speak of the post-Soviet space, which has been completely dismantled as a postcolonial construct. The focus has largely shifted from history to contemporaneity – and what matters now in this contemporary context are Ukraine’s anti-colonial resistance and the production of new narratives, in which art plays a crucial role. After 2022, the decolonial processes and Ukraine’s heartfelt resistance gave a chance to the visibility of its culture, long suppressed by first Russian colonial domination and then by the further postcolonial appropriation of Ukrainian culture by Russia.

In my research, I largely draw on both decolonial theory from Latin America by such theorists as Aníbal Quijano, Walter Mignolo, and Boaventura de Sousa Santos as a methodological basis and my personal experience in the region. I have talked in detail about my work for Ukrainian cultural diplomacy through a comparative approach in my recent text for the Mexico Institute blog at the Wilson Center. Since 2014, I have extensively worked on this transatlantic Ukraine/ Latin America comparative perspective both in theory and practice. In 2019, I co-curated At the Front Line. Ukrainian Art, 2013-2019/ La línea del frente. El arte ucraniano, 2013-2019, the first large-scale interdisciplinary project focusing on Ukraine in Latin America. It included a five-month-long exhibition showcasing Ukrainian artists at the National Museum of Cultures in Mexico City, performances by Mexican artists in response to the topics of war and displacement, documentary screenings at the National Cinematheque, and a series of conferences at the Museum of Memory and Tolerance in Mexico City. This exhibition attempted to overcome the political and cultural gap creating a dialogue with Mexican audiences. When speaking about the 2013/2014 Euromaidan protests, for example, we received a strong response from the local public who remembered or even witnessed the Tlatelolco massacre in 1968. Similarly, the stories of Russian military violence in eastern Ukraine prompted comparisons with the drug cartels’ violent actions in the north of Mexico. The decolonial stance plays a significant role in such a comparison, and I believe that the Latin American experience can contribute to a broader understanding of Ukraine’s decolonial processes.

Q: Why do you believe that your research matters to a wider audience?

I believe that my research – as well as the research by my colleagues who work with decolonization and decoloniality – is crucial for the understanding of the new social and political reality Ukraine has been immersed in since 2014. This anti-colonial struggle was further actualized by the necessity of resistance to the full-scale invasion in 2022 and had its important effects on the global political situation, particularly in the West. These changes in the perspective outline the urgency of decolonization of studies on Ukraine, Russia, and the region, in order to resolve historical injustices of Russia’s postcolonial domination in the education and cultural sphere. The only way to do this is to make Ukraine’s own achievements visible and further foster the process of cultural production. In my research, I show how the expanded knowledge constituted by extant artistic documentation of Russia’s war against Ukraine further served as an epistemological foundation for fully disentangling from Russian colonial narratives after 2022. Art production is an important channel for decolonial processes. And these processes have direct effects on a wider audience, both inside and outside Ukraine. I aim to describe the ongoing processes of decolonization in Ukrainian culture not through binary oppositions only, but as a more comprehensive and inclusive, all-involving change in Ukrainian society that we are witnessing now. I also believe that the development of a relevant theoretical background will help develop strategies for decolonization that would reflect on Ukraine’s current political and social situation with regard to its contested history and uneasy contemporaneity.

Q: What is the most challenging aspect of your research?

The most challenging aspect of my research is finding the right words, the appropriate terminology, as well as the correct methodology for talking about Ukraine’s resistance to the Russian invasion and its decolonial release as reflected in culture. The situation in Ukraine is largely unique vis-à-vis the cases analyzed by both postcolonial and decolonial theorists for several reasons: the shared border with the former colonial state, the anachronic recreation of the imperial ambition and the colonizer’s position by Russia in a time when the empires of the world have fallen, and Russia’s current exploiting of the Soviet Union’s Cold-War-time propaganda narratives of anti-imperialist struggle, among others. This situation is different from most known colonizer/ colonized models and it requires a thorough analysis and description through the elaboration of a new theoretical approach – which will be useful also in an application to other countries of the former Soviet space which suffered from Russian colonialism. I aim to contribute toward this aim with my upcoming monograph, in which I present several theoretical proposals.

Q: What do you hope the impact of your research will be?

I hope that my research will eventually contribute to the development of a new model of looking at Ukrainian culture and help find an appropriate niche for it in both academia and cultural practice. Ukrainian studies in general require further work for their expanded development and visibility after they were overshadowed by Russian studies for decades. I hope also that my focus on showcasing Ukrainian contemporary artists will result in greater international recognition of their work.

The opinions expressed in this article are those solely of the author and do not reflect the views of the Kennan Institute.

Author

Kennan Institute

After more than 50 years as a vital part of the Wilson Center legacy, the Kennan Institute has become an independent think tank. You can find the current website for the Kennan Institute at kennaninstitute.org. Please look for future announcements about partnership activities between the Wilson Center and the Kennan Institute at Wilson Center Press Room. The Kennan Institute is the premier US center for advanced research on Eurasia and the oldest and largest regional program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Talking to the Dead to Heal the Living

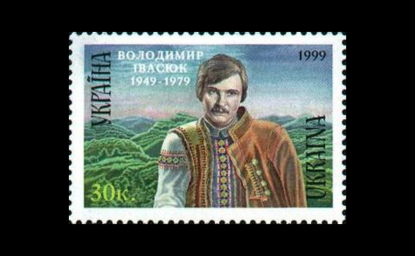

Mustached Bards: Revisiting Soviet Ukrainian Pop Music

Creating Rules of the Game for Contemporary Ukrainian Theater