On Wednesday morning, May 18, 2022, the Finnish Ambassador to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), Mr. Klaus Korhonen and the Swedish Ambassador to NATO, Mr. Axel Wernhoff, handed in Finland and Sweden’s official letters of application in the Alliance’s Brussels headquarters. The applications were filed after months of national domestic debates on both sides of the Gulf of Bothnia following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24. In his remarks, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg welcomed the requests, saying “this is a good day, at a critical moment for our security.” He continued, “every nation has the right to choose its own path. You have both made your choice, after thorough democratic processes. … NATO is already vigilant in the Baltic Sea region, and NATO and Allies’ forces will continue to adapt as necessary.”

At the eve of the Madrid NATO Summit on 28-30 June 2022 the final outcome was far from certain, as an ascension of any country to the alliance will need to be unanimously accepted by all members. Previously the Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan had threatened to veto membership talks in response to Finland and Sweden’s refusal to extradite alleged members of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), which is designated as a terrorist organization by the US, and the EU. To mitigate risks during the precarious ascension period, Finland and Sweden sought and received security guarantees from France, Germany, the United States and the United Kingdom. However, ahead of the NATO leader’s Summit, Türkiye lifted its opposition to Finland and Sweden’s NATO bid after long negotiations and signed a trilateral memorandum to support the invitation of the countries to NATO.

This report aims to provide insights into how Finland and Sweden’s prospective NATO membership would change the military and political landscape of the Baltic Sea region. The report (i) summarizes key Finnish and Swedish military expenditures in recent years, detailing current projects; (ii) discusses bilateral defense cooperation between Finland and Sweden; (iii) sheds light on a case study, Finland’s acquisition of the combat aircraft F-35 in 2022; and finally, (iv) situates the two Nordic countries in the Baltic Sea region’s security framework.

Baltic Sea region in the post-Cold War era

The Baltic Sea region stretches from northern Finland in the north to northern Germany in the south and the Danish straits in the west. On the eastern border of the region lies St. Petersburg, Russia’s second largest city, on the shore of the Baltic Sea. The region is home to approximately 85 million people residing in eight EU member states (Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Sweden) and, as a core European economic-political region, generates almost a fifth of the EU’s GDP. Because of its vital economic significance for Europe, a functioning and self-sufficient national and regional security is of critical importance to the stability of the area.

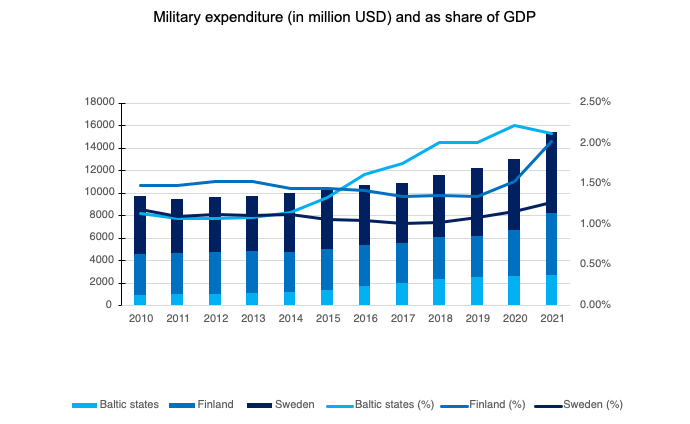

The report begins with an overview of Finnish military expenditures. In the early 1990s Finland purchased 64 F-18 fighter jets in a hallmark acquisition of US-manufactured military technology. This acquisition marked a groundbreaking change, previously Finland alternated between Soviet and Swedish produced aircrafts. Over the past two decades, Finland has gradually increased its defense spending; Finnish defense spending was at its lowest point in the early 2000s (around 1.2 percent of GDP), while today it exceeds 2 percent. The growth rate of Sweden’s military expenditure in recent years has been much flatter as seen in Figure 1.

After Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, the countries in the Baltic Sea region have firmly increased their commitment to security. The combined military expenditures of Sweden, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania increased from 10 billion dollars in 2014 to 15 billion dollars in 2021. During this period, Latvia and Lithuania doubled their defense budget to over 2 percent of their respective GDP. Finland and Sweden - much larger economies as measured in GDP than the Baltic states combined - would significantly contribute to the collective defense of the Baltic Sea region.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 prompted strong responses by European leaders all over the continent. Germany’s pledge of investing 100 billion euro in defense spending ($110 billion USD) marks a major policy shift and reversal of Germany’s decades-long trend of reducing military expenditures. More European countries - Belgium, Romania, Poland, Italy, Latvia, Estonia, Norway, Sweden and Finland - announced increased defense budgets for the fiscal year 2022.

In 2022, the military budget for Finland is approximately 6 billion dollars and Sweden’s budget is 8 billion dollars. The Finnish Ministry of Finance is proposing an additional 1.1 billion EUR ($1.2 billion USD) spending increase (May 6, 2022) due to changes in the operational environment after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The Finnish General Government Fiscal Plan for 2023-2026 allocates a yearly increase of 408-788 million EUR ($431-833 million USD) for the Defence Force’s operating costs and procurement expenditure totalling 2.2. billion EUR ($2.4 billion USD) for the period. In March 2022, the Swedish government announced that it will boost its defense spending by approximately 3 billion Swedish crowns ($320 million USD) for this year. In the future, Sweden’s military expenditures are expected to increase by 40 percent (to approximately $12 billion USD) by 2025. According to the Swedish Armed Forces, Sweden’s defense budget should reach 2 percent of GDP in 2028. This increase in defense spending further underscores Finland and Sweden’s commitment to increase Baltic Sea region security.

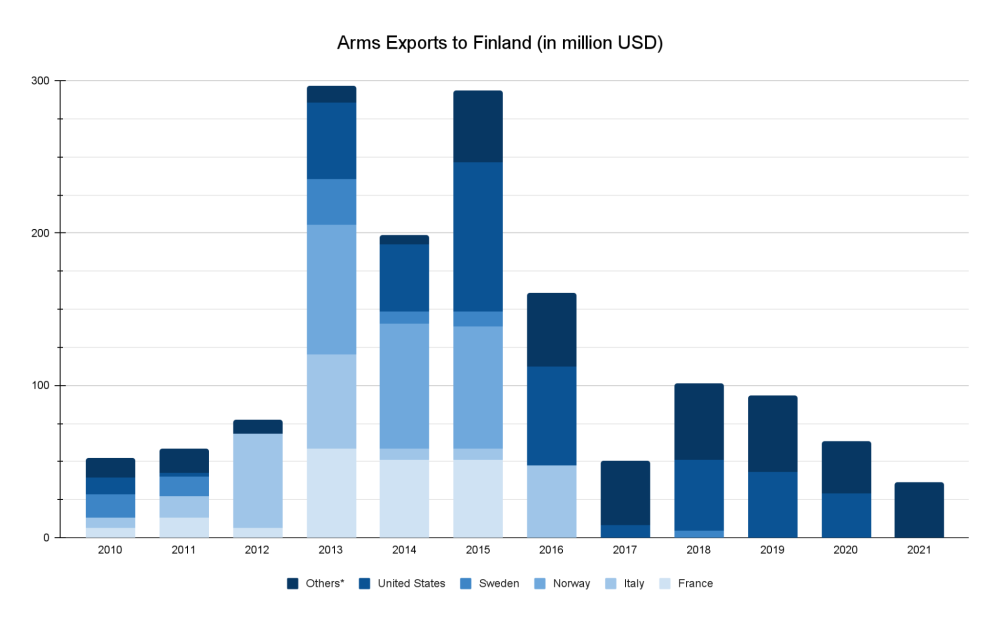

While both Sweden and Finland have a credible domestic production of arms for security, international procurement is essential. NATO membership is likely to strengthen the two countries’ access to international arms markets and would open opportunities for greater specialization and collaboration. In terms of market dynamics, the Nordic defense markets are competitive. In Finland, Patria - the mostly state-owned provider of defense, security and aviation support services - serves domestic demand together with some 120 small-medium sized companies. In terms of capabilities, Finnish companies manufacture - among other things - naval ships, maritime surface technology, armored wheeled vehicles, satellites and telecommunications, as well as cybersecurity solutions. Prominent Finnish arms trading partners include the United States, Sweden, Norway, Italy, France, Germany, Netherlands and Israel (Figure 2). In terms of exports, the United States and Sweden ranks among Finland’s most significant partners. Major historical weaponry purchases from the past decade include AGM-158 Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missiles from the United States (2012), Multiple Launch Rocket Systems and Leopard 2A6 main battle tanks from the Netherlands (2014), K9 armored howitzers from South Korea (2017), and most recently 64 F-35 fighter jets from the United States (2022) as well as the renewal of several older sea vessels (Squadron 2020). Furthermore, Finland is preparing to procure anti-air missile equipment from Israel.

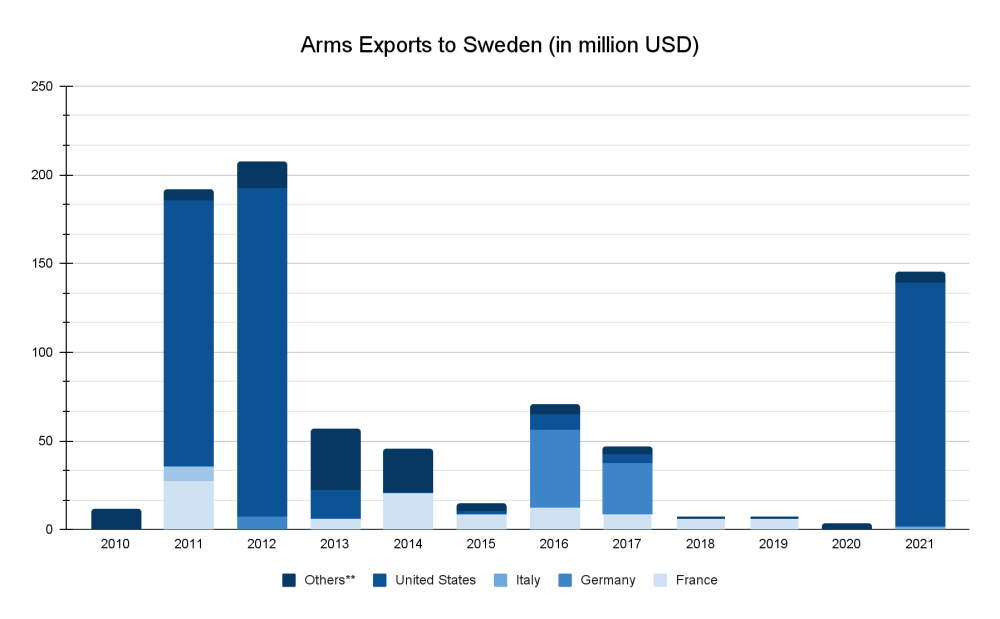

Swedish defense markets are served - together with international partners - by small and medium sized companies as well as larger companies such as Saab, BAE Hägglunds and BAE Bofors. The Swedish arms industry is much larger and more export oriented than the Finnish one, and Sweden is the 13th largest arms exporter in the world. Sweden possesses an advanced, internationally operating aerospace manufacturing industry, and produces fighter aircraft systems, telecommunication solutions, and naval ships. Sweden's largest arms trading partners include the United States, Italy, Germany, France and Canada. Air defense systems and aircraft are among the most important military technologies exported by Sweden. In 2012, Sweden set an order for renewal of its aircraft fleet (60 Saab Gripen jets) that are currently being delivered, in 2021 became the first non-NATO country to deploy a US manufactured Patriot air defense system, and started the procurement process for new combat sea vessels. In 2022, Sweden is expected to increase its number of military personnel, defense capabilities on the Gotland island as well as to commit to buying more Archer 155mm howitzer artillery.

Defense Cooperation between Finland and Sweden

Finland and Sweden have long had close security cooperation as militarily non-aligned Western countries. With shared values and widely integrated economies, both countries joined the EU in 1995, thus ending their status as politically neutral nations. That being said, both countries had previously decided not to join NATO, opting to keep NATO membership as an option. Since the end of the Cold War, Finland and Sweden have shared similar political paths; they differ, however, in terms of their choices related to defense preparedness and spending. Sweden downsized their military capabilities after the collapse of the Soviet Union, culminating in the steep reduction in the number of conscripted servicemen from a peak of nearly 37,000 annual conscripts in 1994, to a low point in 2007 when only 4,730 attended conscription service. Ultimately, Sweden abolished their conscription service during peacetime in 2010, and transitioned to a small yet nimble professional military. Finland, on the other hand, never abandoned their stance of keeping up a credible independent military deterrent. Even though economic downturns, like the financial crisis of 2009, had significant detrimental effects on the Finnish economy and government coffers, the support for a relatively strong, independent conscription-based defense force never waned. The support for mandatory conscription is shared across the whole political spectrum in Finland and commonly argued for on economic (conscription is cost-effective), historic (Finland fought two wars with Russia in the last century) and geographic (shared border with Russia) grounds.

Sweden came to a turning point in its approach to national defense with Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014. That was a wake-up call for most eastern European countries of a possible aggressive Russian foreign policy that included the use of military force to drive its national agenda. Sweden explicitly linked its increase in national security resource allocation to Russia’s military assertiveness. This led to Sweden increasing its military spending and a partial reactivation of mandatory military service. Simultaneously, this development led to a new form of enhanced bilateral Swedish-Finnish security collaboration. This alignment in thinking and resources was based on a shared situational awareness of the increased Russian threat and an understanding of the need for broader and deeper military collaboration, which was not achievable through the European Union in the short term.

In 2014 Finland and Sweden already shared similar security policies, and many forums for collaboration, including through the United Nations, Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), Nordic Defense Cooperation (NORDEFCO), civil security collaboration, the EU’s defense collaboration, and NATO’s Partnership for Peace for non-member collaboration. However, the bilateral security and defense collaboration journey that the countries started upon went much deeper than any of these previous forms of multilateral collaboration. In 2014, Helsinki and Stockholm published a political action plan, which was followed by a joint report by the Finnish Defence Forces and the Swedish Armed Forces that set a vision for the shared use of naval bases, mutual support for and the partial integration of their respective air forces, and the development of a combined Finnish - Swedish Brigade Framework that included force integration and interoperability. The report highlighted the need for bilateral agreements, the political mandate and legal arrangements that were needed to achieve this shared vision. Since then, Sweden and Finland have signed many defense cooperation agreements, including a memorandum of understanding on defense cooperation (2018), host nation support for military activities (2022), and military strategic concept for deepened defense cooperation (2019) to ensure that no legislative hurdles put any objections to military cooperation when needed.

The development in these agreements has made military cooperation possible beyond peace, which previously was not part of any multilateral collaboration of the countries. The stated objective is to create permanent conditions for military cooperation and joint operations covering times of crisis, conflicts, and war, without any pre-set restrictions for intensified bilateral cooperation. The plans set in motion in 2014 have already borne fruit, including the establishment of a brigade-size common training exercises for Finnish and Swedish army troops, the Swedish Finnish Amphibious Task Unit (SFATU), and the Swedish-Finnish Naval Task Group (SFNTG) which will reach full operational capability by 2023. Furthermore, Finland and Sweden train actively in joint exercises together and with other allies, of which the ongoing Baltic Operations BALTOPS22 hosted by Sweden is the most recent with over 45 ships, 75 helicopters or aircraft, and over 7,000 personnel from 14 NATO allies and two partners. The two countries have also recently agreed on joint procurement on military systems, such as the new Nordic combat uniform, small firearms and collaboration on R&D program for a common armored 6x6 vehicle system. These developments not only enhance the operational capabilities of these two countries, but also publicly confirms the political alignment on a common security of the two nations.

Case Study: The Finnish Fighter Jet F-35 Project Explained

The Finnish Defence Forces have a long history of close cooperation with NATO - in addition to the United States and neighboring Nordic countries. As Finland chose to replace its current fighter aircraft, the F/A-18 Hornet, with F-35 Joint Strike Fighters from the United States, this cooperation has deepened further and provides an opportunity for enhanced airpower collaboration among the Nordic states. The F-35 variants stand out as a front-runner for most recently announced fighter jet procurement deals for several European NATO countries. The Finnish F-35 project (previously called the HX program), launched in 2015, was started to replace Finland’s current fighters at the end of their life-span by 2030. Requests for information on multi-role fighters were originally sent out in 2016 to the defense administrations of the United Kingdom (Eurofighter Typhoon), France (Dassault Rafale), Sweden (Saab JAS E/F Gripen) and the United States (Boeing F/A-18E/F Super Hornet and Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II). Based on a thorough tendering process and comprehensive testing, the Finnish government made the decision to procure the Lockheed Martin fighter jets.

The deal signed in February 2022 is worth a total of 8.4 billion euro ($8.9 billion USD) and it is the largest military procurement deal ever made by Finland and one of the largest in Europe. The contract includes 64 F-35A Block 4-multi role fighters to be delivered during 2025-2030 (EUR 4.7 billion; $5 billion USD) equipped with AMRAAM and Sidewinder air-to-air missiles (EUR 755 million; $800 million USD). The rest of the sum is allocated to maintenance and service equipment and services (EUR 2.9 billion; $3.1 billion USD), construction of operational facilities in Finland (EUR 777 million; $820 million USD) and another 824 million euro ($873 million USD) for subsequent contracts and contract amendments.

As part of the deal, an Industrial Participation Agreement was signed with the fighter manufacturer Lockheed Martin and Pratt & Whitney worth at least 30 percent of the actual contract price, approximately 2-3 billion euro. By industrial participation Finland thus ensures the know-how and material needed to operate the fighter jets under exceptional circumstances and adds local technology transfers which will improve the technological capabilities of the Finnish defense industry. Expected to stay in operation until the 2070s, the F-35 procurement marks a long term commitment to deeper cooperation between Finnish and US Air Forces and the American fighter jet industry that has endured since the initial order of F/A-18s in 1992.

The Newest Members to NATO’s Northern Frontier?

Finland and Sweden - two stable Nordic democracies - are the final vital pieces missing from completing NATO’s northern security architecture, where a Finnish and Swedish NATO membership would increase the security of both NATO and the Baltic region. Firstly, geostrategically, Finland has gained over 100 years of valuable experience as Russia’s neighbor, the two sharing a 1,340 km (832 miles) land border. Finland has accumulated valuable intelligence on border activity in the East. The Åland Islands, an autonomous demilitarized region of Finland, together with Gotland, a Swedish island with a military base, are important hubs connecting trade lanes across the Baltic Sea. As members of the Arctic Council, Finland and Sweden have valuable practical insights into operating their societies in sub-Arctic climates with long, cold snowy winters in the north.

Secondly, in addition to their critical geostrategic locations, Finland and Sweden as countries are technologically advanced with leading solutions in 5G-technologies and cybersecurity. As prospective NATO members, Finnish and Swedish domestic small and medium sized enterprises with cutting-edge solutions in the defense, aerospace and security sector would have enhanced preferential access to national procurement processes at NATO’s Conference of National Armaments Directors (CNAD). With seats at the right tables, companies would get their products to market faster and more cost effectively, benefitting the whole Alliance. As countries across the transatlantic sea renew their capabilities as a result of a changed security reality, there is a renewed demand for Finnish and Swedish technology.

And thirdly, Finland has valuable military leadership know-how generated from its national conscription since the beginning of the 20th century. Finland and Sweden have the capability to maneuver and maintain operations in both Arctic conditions on land and in the sea, as well as control the skies in the northern Baltic Sea region. Moreover, as close partners of NATO over two decades, with frequent experience of conducting military exercises together - Finnish and Swedish armies are NATO compatible and interoperable.

The northern expansion of NATO would push NATO’s eastern border closer towards two important Russian cities; St. Petersburg, which has an important seaport, and secondly the important military base of Murmansk, where the Russian Northern Fleet with its nuclear submarines resides. The new border would enable a new ring of defense for the whole Western Europe as anti-air capabilities and early-warning detection could be based nearer to the Alliance’s border.

Conclusion

This report has laid out what a Finnish and Swedish NATO membership would bring to security in the Baltic Sea region. As two technologically advanced and resilient societies, NATO has much to gain from Finnish and Swedish membership. Net security contributors in terms of advanced military capabilities, Finnish and Swedish navy and airforce power add to the collective defense in both Baltic Sea region as well as in the Arctic. Finland and Sweden, respectively, benefit from increased security alignment with the defense alliance and its security guarantees.

As described in the report, the Finnish and Swedish military expenditures and materiel procurements are large in comparison to the smaller Baltic countries and have been increasing in recent years, especially since Russia's invasion of Ukraine. The membership and deeper co-integration thus opens new opportunities for the defense and support of the Baltic states as well.

Finland and Sweden have unequivocally signaled their interest to join NATO as a result of Russia’s attack on Ukraine. With the threat of a Turkish veto for the ascension now lifted and having thus received the support of all existing NATO member states it seems plausible that fast-tracked negotiations and ascension are feasible. The enlargement will bring NATO to Russia’s doorsteps and more than double its border with the Alliance, which is undeniably not in Russia’s interest. The words of Finnish President Sauli Niinistö: “You caused this. Look in the mirror.” will certainly ring true.

Authors

Global Europe Program

The Global Europe Program is focused on Europe’s capabilities, and how it engages on critical global issues. We investigate European approaches to critical global issues. We examine Europe’s relations with Russia and Eurasia, China and the Indo-Pacific, the Middle East and Africa. Our initiatives include “Ukraine in Europe”—an examination of what it will take to make Ukraine’s European future a reality. But we also examine the role of NATO, the European Union and the OSCE, Europe’s energy security, transatlantic trade disputes, and challenges to democracy. The Global Europe Program’s staff, scholars-in-residence, and Global Fellows participate in seminars, policy study groups, and international conferences to provide analytical recommendations to policy makers and the media. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Trump Speaks with Putin in Effort to End Russia-Ukraine War

From Partner to Ally: Sweden’s First Year in NATO

“Security, Europe!”: Poland's Rise as NATO's Defense Spending Leader