Explainer: Rival Islamists in 2022

An overview of Islamist rivalries by Cole Bunzel, a fellow at Stanford University's Hoover Institution.

An overview of Islamist rivalries by Cole Bunzel, a fellow at Stanford University's Hoover Institution.

Islamism is an umbrella term for a complex spectrum of groups. It covers political parties, such as the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and Ennahda in Tunisia, as well as militant movements like al Qaeda and the Islamic State. The term comes from the French islamisme, which originated as a synonym for the religion of Islam. It was repurposed in the 1980s by Western scholars, such as Gilles Kepel, as an alternative to the more problematic misnomer “Islamic fundamentalism.” It soon crossed over into English usage.

Modern Islamist movements date to the early 20th century in the Arab world. Defining Islamism is disputed due both to the nature of Islam and the variety of Islamist actors. Some scholars emphasize a dichotomy between modern Islamism, understood as a threatening political ideology, and Islam, understood as a benign religion. Yet Islam has been deeply entwined with politics since it was founded in the seventh century. Mohammed was at once a prophet, a politician and a military commander, a combination reflected in Islamic traditions that developed over more than a millennium. Islamic legal manuals include prescriptions on the ideal Islamic polity, the ideal conduct of its ruler, and the proper prosecution of military campaigns (both defensive and offensive).

The term’s utility, however, lies in understanding the common commitment of disparate Muslim groups to assert and empower their versions of Islam within state structures that are modern and Western in origin. Beyond this shared characteristic, Islamism features a diverse tapestry of ideologies that often pit groups against each other. The two basic categories are mainstream and militant Islamism. They differ in practices, goals, and tactics—and do not believe they belong to the same type of movement. Some are generally nonbelligerent, while others practice ruthless violence. Some even view rivals as infidel apostates who should be killed if they don’t adhere to their interpretation of the faith.

Modern Islamism originated in the Society of Muslim Brothers (or Muslim Brotherhood), which was founded in Egypt by Hassan al Banna in 1928. He sought to revive the social and political norms derived from Islam as modernity and Western imperialism unsettled centuries of Islamic traditions. He viewed Islam as an all-encompassing system to cover both religion and governance. By the 1940s, the Muslim Brotherhood had become a grassroots movement spawning branches in other Arab states.

The Brotherhood’s success was also a liability, as Egypt’s successive authoritarian rulers—from Gamal Abdel Nasser (1954 to 1970) to Hosni Mubarak (1970 to 2011)—clamped down on it. In response, some Brotherhood leaders in the 1950s and 1960s espoused a more violent and confrontational approach to achieving Islamist objectives. With that exception, however, the Muslim Brotherhood has generally renounced revolutionary dogma. It has advocated political gradualism, eschewal of violence as the primary recourse for change, and a willingness to work within existing institutions, such as an elected parliament or trade guilds. The Brotherhood has come to represent mainstream Islamism.

Militant Islamism has roots in the legal and theological tradition of Salafism, a purist movement associated with the teachings of Ibn Taymiyya in the 14th century and his heirs in the Wahhabi movement that emerged in Arabia in the mid-18th century. Modern militancy dates to the revolutionary ideas of Sayyid Qutb, who was executed by the Egyptian regime in 1966. Unlike their mainstream cousins, militant Islamists believe that jihad—or “to struggle” —is necessary to facilitate change and capture the state. Militants reinterpret jihad to mean revolutionary violence against a despotic ruler deemed an apostate. The emphasis on jihad created the moniker “jihadis.”

Jihadis often declare other Muslims who fail to join their movements to be kuffar (or unbelievers). Militants reject the Muslim Brotherhood as a political failure. They view democracy to be shirk, or “polytheism,” since it empowers the laws of man over the law of God, or Sharia.

In the 1970s, Egypt witnessed the emergence of militant Islamist groups seeking to destroy the state through terrorist attacks, including the assassination of President Anwar Sadat in 1981 for making peace with Israel. In his 1988 book “The Bitter Harvest,” Ayman al Zawahiri, an Egyptian who succeeded Osama bin Laden as leader of al Qaeda, condemned the Brotherhood for embracing democracy and working with “apostate” dictators. In June 2022, the jihadi scholar Abu Huzayfa al Sudani denounced Muslims who left the “righteous path” for pacifist politics that relied on democratic votes to elevate them to power. The basic difference between mainstream and militant Islamism is not the only split.

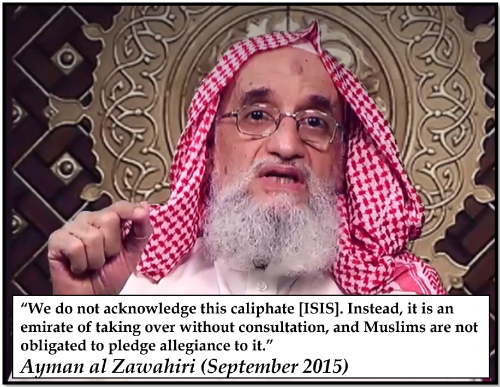

In the 21st century, the jihadi movement has increasingly divided into two major trends, reflected by the rivalry between al Qaeda and the Islamic State. Both are radical and seek to create a caliphate. But they diverge over basic strategy and their relationship with other Muslims.

Formed in Pakistan in the late 1980s by Osama bin Laden, al Qaeda developed into a global terrorist organization in the 1990s. Bin Laden emerged as the central figure in the diverse world of jihadism. Al Qaeda prioritized attacks on the United States and its interests. The primary goal was to force the United States to withdraw from the Middle East and South Asia, thereby opening the way for local jihadi actors to challenge despotic regimes propped up by Washington—and then create local support and eventually Islamist states.

But al Qaeda tried to create distance from more radical jihadis after bin Laden’s death in 2011 and the rise of the Islamic State in 2014. Al Qaeda has portrayed itself to other Muslims as a more moderate jihadi option. Under al Zawahiri, the group has tried to appeal to the broad umma, or community, and refrained from declaring fellow Muslims kuffar if they did not join. Al Qaeda has also condemned the Islamic State as a bloodthirsty Kharijite movement, a reference to the early Islamic sect associated with excessive violence and zeal for takfir (pronouncing other Muslims kuffar).

Since 2014, the Islamic State has represented the more extremist wing in the jihadi world. It has adhered fanatically to the purist and exclusivist elements of Salafi doctrine. It was spawned in 2004 by the ideas and practices of Abu Musab al Zarqawi, a Jordanian militant who founded al Qaeda in Iraq. Shortly after his death in a U.S. airstrike in 2006, his followers created the Islamic State of Iraq—the predecessor to the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). In 2014, ISIS seized roughly a third of Iraq and Syria and proclaimed a regional caliphate—the first phase in creating a global Islamic state. It called on Muslims worldwide to pledge allegiance to ISIS; it denounced all other jihadi groups as illegitimate. Its followers have used extreme violence, including beheading, immolation, stoning, and drowning, the vast majority of the victims being Muslims. They have appeared unconcerned about Muslim public opinion.

Further rifts have since emerged within al Qaeda and the Islamic State. The most significant offshoot has been Hayat Tahrir al Sham (HTS), a Syrian group that has controlled most of Syria’s northwest Idlib Province since 2017. HTS, originally known as Jabhat al Nusra, was initially tied to al Qaeda. But in 2016-17, it formally broke from al Qaeda, which led al Zawahiri to accuse it of breaking its oath and betraying the unity of Islam. Since then, HTS has clamped down on al Qaeda loyalists in its territory, sought to cooperate with Turkey, and even appealed to the United States for recognition. At its core, HTS is still ardently Salafi, but it has also started to evolve in ways more akin to the Muslim Brotherhood.

Mainstream Islamists are generally defined by an aversion to violence to achieve religiopolitical objectives, but with notable exceptions, especially in campaigns against forces seen as foreign occupiers. Hamas, which was founded in 1987 during the first Palestinian intifada against Israel, is a prime example.

Hamas grew out of the Palestinian branch of the Muslim Brotherhood, and it initially did not engage in armed struggle against Israel. After the first Intifada, however, Hamas—an acronym for the Islamic Resistance Movement—embraced kidnappings, car bombings, suicide bombings, and later rocket attacks on civilian and military targets. Hamas also initially opposed the political structures of the new Palestinian Authority created after the Oslo Accords between the PLO and Israel in the 1990s.

In 2005, Hamas changed its strategy and competed in the 2006 Palestinian elections. In a stunning upset over long-dominant Fatah, Hamas won more seats. It initially formed a unity government with Fatah but refused to renounce violence against Israel. Political tensions accelerated as both parties formed their own security forces—Hamas in Gaza and Fatah in the West Bank. Sporadic clashes ensued, killing dozens. In mid-2007, Hamas seized control of the Gaza Strip and was stripped of power in the West Bank. Hamas has since sought to strike a balance between governing Gaza and maintaining “resistance” to Israel in periodic attacks.

The second-largest militant group in the Palestinian territories is Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ), which was also founded in the mid-1980s. It was created by former secular nationalists who turned to Islamist ideals and militant tactics. PIJ has continued to bear the imprint of an anti-colonial ideology. Unlike Hamas, PIJ has prioritized armed struggle to the exclusion of politics. PIJ has occasionally coordinated with Hamas on strategy, but it has not been interested in providing social services or participating in the political process. As a result, it has a comparatively small following—some 8,000 members—with “resistance” largely limited to Gaza. Both groups have received funding and arms from Iran, although PIJ has reportedly been more reliant on Tehran.

Other small jihadi groups—such as Jaysh al Islam and Jaysh al Umma—have operated out of the Palestinian territories, especially Gaza. Hamas has tolerated the groups at times, but it has clashed with them sporadically as well. The smaller jihadi factions have generally struggled to operate. They have viewed Hamas as an example of a failed mainstream Islamist movement that too often betrayed jihad and gave in to compromise and conciliation.

The Taliban, which emerged out of an Afghan student movement in the mid-1990s, have represented mainstream Islamism in Afghanistan, though their roots are not in the Muslim Brotherhood but rather in the Deobandi tradition of South Asia. They first assumed power in 1996 after defeating gangs of rival warlords engaged in a civil war. They allied with and facilitated other jihadi groups, notably al Qaeda. In 2001, the Taliban were ousted from power after al Qaeda’s 9/11 attacks on New York and Washington led to a U.S.-backed military operation by the opposition Northern Alliance. The Taliban then went underground and launched an insurgency against the U.S.-backed government.

After two decades of war in Afghanistan, the United States and the Taliban agreed to terms: U.S. and NATO forces would withdraw in exchange for a Taliban pledge not to allow al Qaeda or other jihadi actors to use Afghanistan as a base to attack U.S. interests or allies. (The negotiations did not include the Afghan government or an agreement on how the country would be ruled after a withdrawal.) The Taliban returned to power, ousting the Afghan government, in August 2021 as U.S. and NATO forces withdrew.

During their first year back in power, some Taliban leaders maintained close relations with al Qaeda. More pragmatic members viewed international recognition for the Taliban government as more important than an open alliance with al Qaeda. The Taliban imposed restrictions on al Qaeda activities in Afghanistan, but the U.S. Department of Defense warned in 2022 that the arrangement might be only temporary.

The Islamic State in Afghanistan—another jihadi movement also known as the Islamic State in Khorasan, or ISIS-K—is a Taliban rival. Both groups have sought to create an Islamic state, but the movements have followed rival Islamist theories. ISIS-K is a Salafi movement, while the Taliban subscribe to the Hanafi school of Islam. ISIS-K views the Taliban as infidels who have diverged from the movement’s early roots and share some U.S. goals, including the defeat of ISIS worldwide. Since 2015, ISIS-K has launched dozens of attacks on the Taliban and its allies as well as civilians. In 2022, its following was reportedly small—in the hundreds or low thousands. The ISIS-K affiliation with Salafism could limit further growth. Its followers have been largely in eastern Afghanistan, from where it has run an insurgent campaign on Kabul and beyond.

Learn more about Hamas and how it relates to similarly aligned organizations throughout the region. Read more